Knowledge is not Power

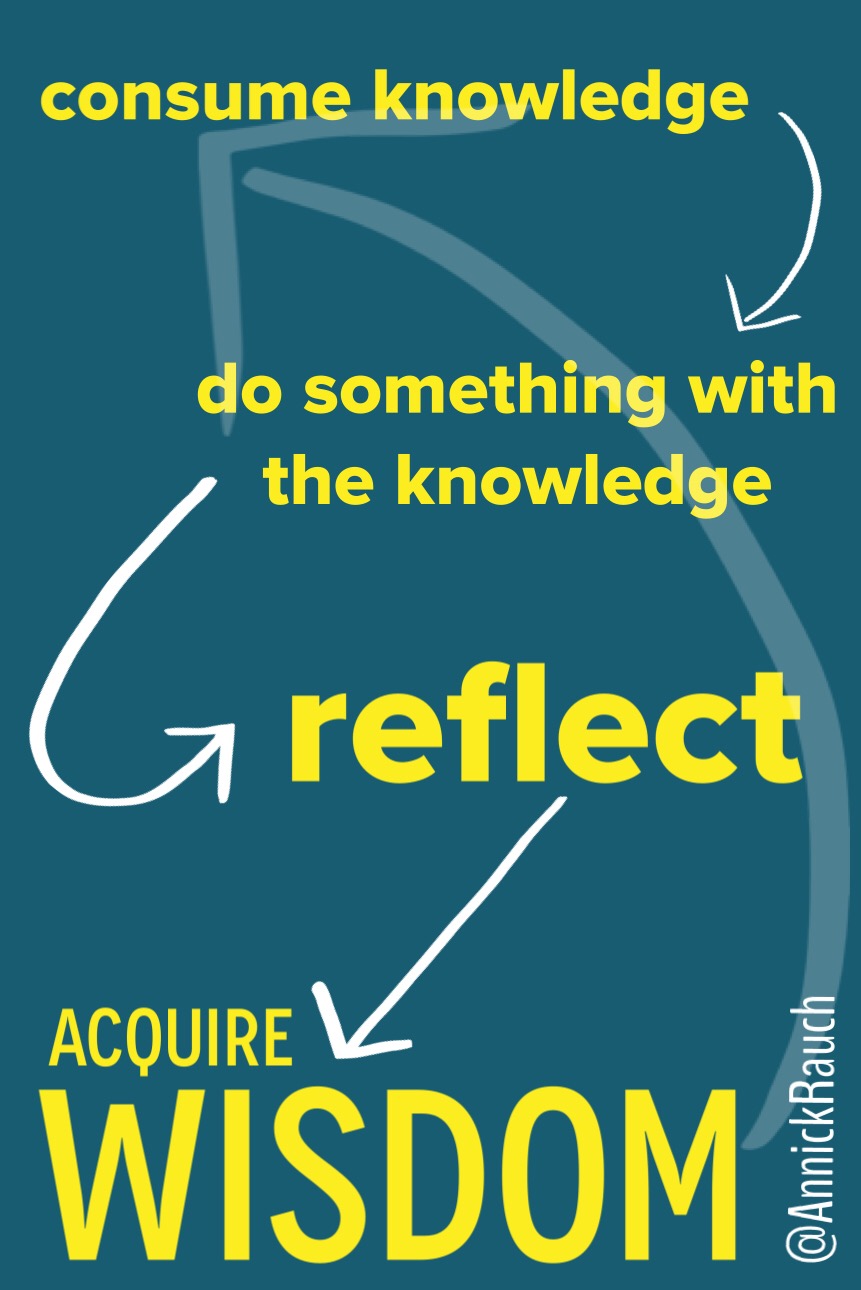

We’ve all heard the saying “Knowledge is power” and although most people tend to nod in agreement, upon further reflection, I would argue that knowledge itself isn’t power… it’s what you do with it that’s can be powerful (or not). When I think of this, two specific examples come to mind.

Think back on your time in university. Have you ever had a professor who was incredibly knowledgeable when it came to his or her content, but didn’t have a clue how to deliver it so that you could take it in? Yeah, me too. Maybe those profs were super knowledgeable when it came to writing research papers, but getting me to learn, nope! Their knowledge did not transfer to power for their learners.

When my first son was born, I was overwhelmed with my lack of knowledge when it came to pretty much everything baby related. I thought I was pretty prepared, but I was not. I had a lot to learn, and I needed time to test things out, relate what I’d been learning to my own situation, and reflect before I felt like I had somewhat of a handle on the simplest of things. It wasn’t until my second was born that I began to gain much more knowledge about car seat safety. Before then, I was still doing everything “right” by following rules and regulations, but turns out, those rules and regulations are, I would say, a “safe enough” mentality at best. I wasn’t okay with “safe enough”, I wanted my children to be as safe as they could be while travelling in the car. I researched and chatted with other moms and came to realize that keeping children rear-facing until they’re 3 years old is the safest approach. I did more research to find a seat that allowed this, as well as fit in my vehicle with a million other car seats (okay – not a million, but 4… I had (and still have) 4 car seats in my van)! I event went as far as to putting a decal on my rear window that said “My toddler rides rear-facing, ask me why!” I had gained knowledge which turned into wisdom as I changed what I was doing in my life to keep my kids safer in a vehicle.

As I thought more about knowledge and wisdom and relating it back to education, I remembered reading this in “Learner-Centered Innovation” by Katie Martin:

“when teachers have structured opportunities to learn and reflect openly about their process, they become more cognizant of how it feels to be a learner.”

That sounds a lot like acquiring wisdom to me.

I also feel like George Couros hit the nail on the head in his post “Developing Wisdom in Schools” which was a timely read for me as all of this was bouncing around in my head:

This [wisdom] is something that we want from our students but in the past, has the system of “school” taken away the application of wisdom from teachers?

In the book, “Practical Wisdom,” Barry Schwartz shares the following observation from the “No Child Left Behind” initiative:

Supporters of lockstep curricula and high-stakes standardized tests were not out to undermine the wisdom, creativity, and energy of good teachers. The scripted curricula and tests were aimed at improving the performance of weak teachers in failing schools—or forcing them out. If lesson plans were tied to tests, teachers’ scripts would tell them what to do to get the students ready. If students still failed, the teachers could be “held accountable.” Equality would seemingly be achieved (no child left behind) by using the same script, thus giving the same education to all students. But this also meant that all teachers, novice or expert, weak or strong, would be required to follow the standardized system.

Teachers on the front lines often point to the considerations left out of the teach-to-test paradigm. Tests are only one indicator of student learning, and poor performance on tests has other causes aside from poor teaching—poorly funded urban schools, students from poor or immigrant backgrounds with few resources at home and sometimes little or no English, overcrowded classrooms with not enough teachers, poor facilities, lack of books and equipment, students with learning problems or other disabilities. But one of the chief criticisms many teachers make is that the system is dumbing down their teaching. It is de-skilling them. It is not allowing them—or teaching them—the judgment they need to do good teaching. They are encouraged, says education scholar professor Linda Darling-Hammond, “to present material that [is] beyond the grasp of some and below the grasp of others, to sacrifice students’ internal motivations and interests in the cause of ‘covering the curriculum,’ and to forgo the teachable moment, when students [are] ready and eager to learn, because it [happens] to fall outside of the prescribed sequence of activities.”

Sooner or later, “turning out” kids who can turn out the right answers the way you turn out screws, or hubcaps, comes to seem like normal practice. Worse, it comes to seem like “best practice.”

If we want to help students acquire wisdom, we must model it. This post isn’t to say that we cannot be wise in our teaching because we have limitations placed upon us, because I assure you there are teachers all around the world that are working within constrains and still knocking the ball out of the park. George refers to this as “innovation inside the box” in his book “The Innovator’s Mindset” and it is all something we should strive towards every day. Our kids are worth it. They deserve our very best every day, just like my own kids deserve to be as safe as they can be while in a vehicle. What are you doing with the knowledge you gain? Are you simply consuming or are you turning it into wisdom?

Leave a Reply